GEORGE RAYA

- Jan 9

- 8 min read

Updated: Feb 1

SOCIETY FOR HOMOSEXUAL FREEDOM, SACRAMENTO GAY LIBERATION FRONT

The Stonewall Riots on June 28, 1969, in New York City, set the earth on fire, and LGBTQ+ people started a new trend called “gay liberation.” Gay liberation was on the cutting edge of social change before it fizzled out a few years later. It was a revolution that was felt near and far. In fact, it swept the entire world. Everything changed.

We now bring you Central Valley boy, George Raya. While we have featured gay activists from across the country, there are a few points that make George’s story interesting. One, he was active in Sacramento, California, which is close to where I grew up. This hits home. Two, the Sacramento State (now California State University, Sacramento) gay liberation group was one of the first in the country, being founded in December of 1969, less than six months after Stonewall. Three, the group was called the Society for Homosexual Freedom. Four, on March 2, 1970, George, a member of the student senate and an early participant in the formation of the SHF, introduced a request for the group to be officially recognized by the university. Six, the university said no, and the group sued the university. Seven, on February 9, 1971, Judge William Gallagher issued a decision in favor of the SHF in the case Associated Students of Sacramento State College v. Butz. This was the first time a gay liberation student group in the United States sued a university for recognition. On top of that, they won! Just like that, the country was altered, and history was made.

— August Bernadicou, Executive Director of The LGBTQ History Project

“It was around seventh grade when I realized I was different. I found my brother's best friend, who was blonde, blue-eyed, and butch-built, attractive. That kind of got me into blonde and butch men. Although I found my brother's best friend very attractive, I never did anything until freshman year of college. In 1968, I actually came out.

My grandparents, both sides, come from Michoacán, Mexico. Well, three of the four are from Michoacán. The fourth one is of Spanish descent in Mexico, but very European. My other relatives were all of that particular tribe from Michoacán. There's a native tribe that was an independent empire from the Aztecs. They actually defeated the Aztecs in civil wars. They never conquered. My mother is very proud that our tribe was an independent empire. Our clan was warriors. Now, I consider myself a Latino.

My family moved to Sacramento in 1966, the day civil rights pioneer Cesar Chavez led a march from Delano, California, to Sacramento, crossing the Tower Bridge to reach the Capitol. I wanted to go down and watch it all, and my grandmother said no, because we never knew how the police were. They're not kind to Mexican protesters. She's right. They weren't back then. They still aren't, in some ways. My family decided that I should go to business school because my older sister had gone to business school, earned a degree in accounting, and worked for the state—working for the state for 33 years, growing up in Sacramento.

I went to business school for a while, and then I decided, no. I really want a four-year liberal arts education. I lucked out because, in the fall of ’68, they started a pilot program at Sacramento State and at UC Davis called the Educational Opportunity Program. I was in the first class, and it was a success. It went statewide in 1969, so most college campuses celebrate EOP as starting in ’69.

I was very active on campus. I was in the student government and got elected to chair of the student senate. I lost my election for president.

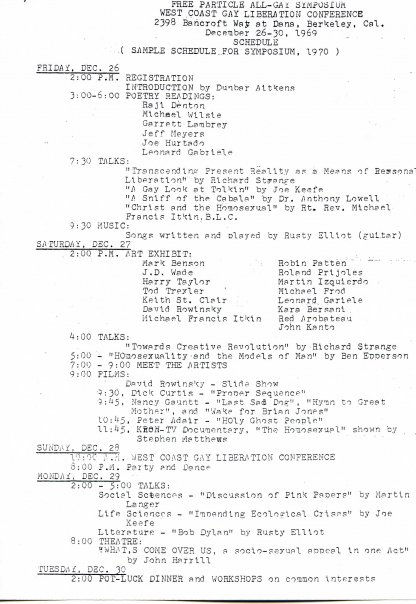

Somehow, I had gotten a flyer for the West Coast Gay Liberation Conference in Berkeley, California. The event was to be held in December of 1969. I was newly out and excited about getting involved in a movement—I had gone to the library when I came out to find out everything about homosexuality—the bibliography at the library. So I went to the little library, and one of the articles I found was about abnormal psychology. There were usually a couple of books, and we were generally under abnormal psychology. But there was one law review article from a journal at California Western School of Law in San Diego, and it was titled Why the Status Quo. Reading that article, it really clicked with me that we have to act.

This was the era of the civil rights movement. There were marches, and the anti-war movement was underway. I had been involved in the Mexican-American movement early in high school. In 66, I started a group called the Maya Mexican American Youth Association, and we were meeting with college students to put on a conference at Sac State to encourage Latino youth, Mexican-American youth, to go on to get a four-year college degree because not a lot of people were encouraging Latinos to get a college education.

Sacramento's had de facto segregation—you could draw a line on Highway 50. You better believe it's a real line, folks, it's a real line. I remember one time they tried to march into East Sacramento. The police met them on the bridge and arrested everybody, including the Sacramento Bee reporter who was with them. It was made really clear that you are not welcome in East Sacramento, so don't even think of crossing the bridge. This was a racist town, and it came right back to me when I went to my 50th high school reunion, class of ’67—’67 was the year that the US Supreme Court said that it was okay for interracial marriage, Loving v. Virginia. Great name for a case, a black and white couple married, which was illegal in the state of Virginia, and so they were prosecuted, and it went all the way to the Supreme Court, and the court said interracial marriage was not illegal.

I went to that December ’69 conference—the West Coast Gay Liberation Conference. I brought back the messages from Berkeley to Sacramento State. We had already formed our group. We decided to call ourselves—in the pre ’70s, pre-Stonewall, most of the organizations that existed did not have the word ‘gay’ or ‘homosexual’ in them. They were the Daughters of Bilitis and the Mattachine Society. There was ONE, Inc. in Los Angeles and the Society for Individual Rights in San Francisco, but we decided we wanted to be upfront. So we were going to call ourselves the Society for Homosexual Freedom. It was to educate the general public about the gay community.

At the conference's Saturday night dance, I saw this very attractive young guy: he has a short haircut, he’s butch, military looking, and he's just watching. He's not doing anything. He's not talking to anybody. So I go up to him, and I say, ‘If you don't dance soon, people are just going to think you're here to spy on us.’ So we dance and get acquainted, and I go home with him, and it turns out he was an undercover military intelligence guy. He was there for the military. They were keeping an eye on us. The Bay Area had lots of military bases, which is why the military sent someone to investigate the conference.

I was in the student senate, chair of the committee that approved all new class and club organizations. I got us a charter approved by the student senate. My committee approved. It went to the full senate. Then it was approved automatically by the full senate. Under normal circumstances, if the student senate approves a new campus organization, the college president rubber-stamps it and grants it a charter. But in this case—we had an acting college president named Otto Butz, and Ronald Reagan was our current governor. Otto felt that if he approved a gay student group for Sac State, Ronald Reagan would make sure that the board of trustees would not appoint him to be president on a permanent basis. It was a strictly political decision.

We went to the student government and said, ‘This is a student rights case.’ And they agreed. But a friend of mine, who I served with on the student senate, reminded me that it wasn't a clear-cut vote. It was a split. It was a real close vote, five, seven, something like that. So the student government sued, and we hired a former student body president who had just freshly been minted as an attorney at UC Berkeley, John Poswall. He took the case primarily because back in those days, attorneys were forbidden to advertise. The only way you could really build your practice was to get a good case that got you in the press and earned you significant notoriety. He looked at this case, and he said, ‘This is going to be a newsworthy case, so it'll get me in the paper. Great.’ He took the case, won it, and it made his name. We won our case, and this was the first of its kind in the country. We set a precedent.

We did a week-long symposium in the spring of ’71 on homosexuality. Here, we were, this little backwater college, doing something no other school was doing at the time, having a week-long symposium on homosexuality, and the faculty was doing the organizing. It was decided we needed a keynote speaker, someone with national name recognition. They went down a list of names, and they came up with Allen Ginsberg. They only had $300 for an honorarium. So we wrote to him and said, ‘Mr. Ginsburg, we can only offer you a $300 honorarium, but while you are on the Sac State campus, we can guarantee you student companionship.’ He flies in. The faculty told us the story: Ginsburg's in the backseat, leans on the seat, and says, ‘Your letter said, student companionship.’

The night before, the Society for Homosexual Freedom had a meeting, and Edgar Carpenter, who was our then president, said, ‘Okay, boys, we need a volunteer.’ In the back, this little guy goes, ‘Me, me, me, me, me, me.’ Turns out he was a poet and wanted to meet Ginsburg. And so we said, ‘Okay, you're it.’ Well, Ginsburg was more than happy. He was not only happy, but he also took the guy to San Francisco and introduced him to Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who ran City Lights bookstore in San Francisco. City Lights eventually published some of his work.

Ginsburg—the performance he gave—Sac State men's gym, at that time, was the biggest building on campus. It held the most people, and it was packed to the rafters. He gave a full Ginsburg. We got the full Ginsburg. He walks in, being preceded by young men with ringlets of flowers in their hair, tossing rose petals in his path. You know, beautiful, beautiful. Then they had set up a low stage with Persian carpets and his squeeze box and a microphone—he omed, and he chanted, and then he read one of his poems, Please Master, an S&M poem. He read his poetry, he omed, he chanted, he did everything but dance. We had dancing boys for that. But I loved it. I loved it.

The Society for Homosexual Freedom sponsored a coffeehouse on the weekends in downtown Sacramento to give underage folks a place to go. In our meetings, whenever someone knocked, we would freeze, thinking it was the police. It was either the police coming to arrest us for meeting, or someone coming to attend the meeting. I mean, there was fear in the room.”

Related Stories

About The LGBTQ History Project

The LGBTQ History Project is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit preserving the lives and legacies of LGBTQ+ activists from the first wave of gay liberation through oral histories, archives and the QueerCore Podcast.

Comments